A NY Times article reports that the median hourly wage for American workers has declined 2 percent since 2003, after factoring in inflation. The drop has been especially notable, economists say, because productivity — the amount that an average worker produces in an hour and the basic wellspring of a nation’s living standards — has risen steadily over the same period.

A NY Times article reports that the median hourly wage for American workers has declined 2 percent since 2003, after factoring in inflation. The drop has been especially notable, economists say, because productivity — the amount that an average worker produces in an hour and the basic wellspring of a nation’s living standards — has risen steadily over the same period.

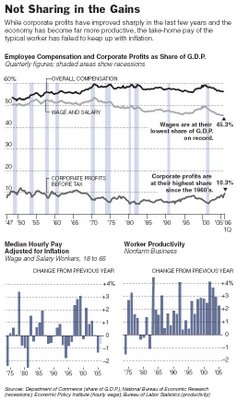

As a result, wages and salaries now make up the lowest share of the nation’s gross domestic product since the government began recording the data in 1947, while corporate profits have climbed to their highest share since the 1960’s. UBS, the investment bank, recently described the current period as “the golden era of profitability.”

Until the last year, stagnating wages were somewhat offset by the rising value of benefits, especially health insurance, which caused overall compensation for most Americans to continue increasing. Since last summer, however, the value of workers’ benefits has also failed to keep pace with inflation, according to government data.

At the very top of the income spectrum, many workers have continued to receive raises that outpace inflation, and the gains have been large enough to keep average income and consumer spending rising.

Economists offer various reasons for the stagnation of wages. Although the economy continues to add jobs, global trade, immigration, layoffs and technology — as well as the insecurity caused by them — appear to have eroded workers’ bargaining power.

Trade unions are much weaker than they once were, while the buying power of the minimum wage is at a 50-year low. And health care is far more expensive than it was a decade ago, causing companies to spend more on benefits at the expense of wages.

Together, these forces have caused a growing share of the economy to go to companies instead of workers’ paychecks. In the first quarter of 2006, wages and salaries represented 45 percent of gross domestic product, down from almost 50 percent in the first quarter of 2001 and a record 53.6 percent in the first quarter of 1970, according to the Commerce Department. Each percentage point now equals about $132 billion.

Total employee compensation — wages plus benefits — has fared a little better. Its share was briefly lower than its current level of 56.1 percent in the mid-1990’s and otherwise has not been so low since 1966.

Over the last year, the value of employee benefits has risen only 3.4 percent, while inflation has exceeded 4 percent, according to the Labor Department.

For most of the last century, wages and productivity — the key measure of the economy’s efficiency — have risen together, increasing rapidly through the 1950’s and 60’s and far more slowly in the 1970’s and 80’s.

But in recent years, the productivity gains have continued while the pay increases have not kept up. Worker productivity rose 16.6 percent from 2000 to 2005, while total compensation for the median worker rose 7.2 percent, according to Labor Department statistics analyzed by the Economic Policy Institute, a liberal research group. Benefits accounted for most of the increase.

The most recent recession ended in late 2001. Hourly wages continued to rise in 2002 and peaked in early 2003, largely on the lingering strength of the 1990’s boom.

Average family income, adjusted for inflation, has continued to advance at a good clip, a fact Mr. Bush has cited when speaking about the economy. But these gains are a result mainly of increases at the top of the income spectrum that pull up the overall numbers. Even for workers at the 90th percentile of earners — making about $80,000 a year — inflation has outpaced their pay increases over the last three years, according to the Labor Department.

“There are two economies out there,” Mr. Cook, the political analyst, said. “One has been just white hot, going great guns. Those are the people who have benefited from globalization, technology, greater productivity and higher corporate earnings.

“And then there’s the working stiffs,’’ he added, “who just don’t feel like they’re getting ahead despite the fact that they’re working very hard. And there are a lot more people in that group than the other group.”

In 2004, the top 1 percent of earners — a group that includes many chief executives — received 11.2 percent of all wage income, up from 8.7 percent a decade earlier and less than 6 percent three decades ago, according to Emmanuel Saez and Thomas Piketty, economists who analyzed the tax data.

Listen to more here at NPR

Share ideas that inspire. FALLON PLANNERS (and co-conspirators) are freely invited to post trends, commentary, obscure ephemera and insightful rants regarding the experience of branding.

Monday, September 04, 2006

Trend: Bankrupt!: Real Wages vs Productivity

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment